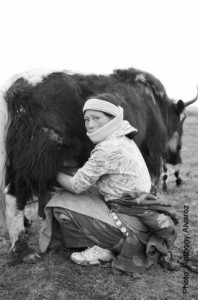

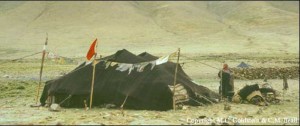

Among the popular global portrayals of Tibetans, it is probably the image of a nomadic yak herdsman standing amongst his livestock beside traditional black tents which is most resonant. It is estimated that twenty five percent of Tibetans are nomads, relying on livestock and the land to thrive in some of the harshest and highest terrain on earth. Despite this near-global fame it is no secret that this traditional way of life is threatened by Chinese domestic policy.

In January 2011, official media outlets in China reported that 1.43 million nomadic farmers had been resettled into new state-provided housing. This move, like many Chinese policies with regards to Tibet, comes under the umbrella of improving the economic welfare of the average Tibetan. Recent relocations stand as an indication of Chinese continuation of this policy which, according to a 2007 report by Human Rights Watch, aims to resettle nomads, confiscate land and fence off areas previously open to migrating animals. Loosely termed, this forms a part of a “Western Development” program to bring about sweeping economic improvements within Tibet, at any and all cost.

In bringing about these changes, it becomes easy for the Chinese state to demonstrate their own successes as reform brings about changes which on the surface can look positive or progressive to outside observers. Despite assurances from Chinese authorities that when moved, people have greater access to social and medical services, Prof. Andrew Fisher from the Institute of Social Studies in the Hague reiterates the concerns of many – that “there is also Han Chinese migrants moving to urban areas (in Tibet) where the economy is dominated by the Chinese”, leading to intense competition for many newly relocated Tibetans in what is, to them, a largely alien environment.

It is evident that economic drivers are not the only justification for the forced resettlement of nomads. According to Chinese state literature, 90 percent of China’s 998 million acres of fragile grassland shows some evidence of degradation, with the nomadic groups who have traditionally made this environment their home being blamed. Despite these figures, environmental justifications for resettlement are perhaps the most questionable, given “the government’s enthusiasm for infrastructure development projects, such as mining, in the very same areas”. Nomadic herdsman continually stress a harmony with nature, and have done so for thousands of years. It would be completely counter-intuitive for the nomadic farmers to overgraze as the Chinese claim, as “maintaining the correct herd size… and avoiding overgrazing, was key to prospering and sustaining life”.

Just what is the reason for the resettlement therefore? Critics of the Chinese regime have been quick to point to the greater struggle by the Chinese authorities for control against the “Dalai Clique”, Tibetan hearts and minds. If this is the case, then the continued Chinese resettlement project takes on an entirely more sinister nature, and stands alongside what many see as a wide push to eradicate or irreparably alter Tibetan culture, and silence the thorn-in-the-side dissent which has come to typify the Tibetan struggle.

Beyond the fact that many relocations have occurred without legal transparency, compensation or consultation, the prospect of a “sedentary lifestyle” is counter to the nomadic culture and tradition and is creating a crisis of suffering amongst the newly formed urban communities. Recent protests, including numerous self-immolations and the recent arrest of 21 Tibetans following demonstrations, highlight the fact that urban poverty seriously undermines previous cultural values and spirits. These tensions also demonstrate a wider Tibetan grievance, that infrastructure and investment don’t necessarily translate into happiness and wellbeing, especially when a culturally rich, self-sufficient culture and population is at stake.

Whatever the arguments, critiques, attacks and rebuttals on both sides of the debate may be, this is the very real situation now for a great number of nomadic peoples in Tibet. The gap between state information and reality may be open to question, and rightfully so, but most pressing now is the plight of the nomads. When a state stands to gain so much in the way of environmental resources, and cultural and social control, the focus should always be on the victims. That “development cannot be simply measured in Yuan”, is the greatest ongoing issue and will continue to be a source of tension.

Print

Print Email

Email