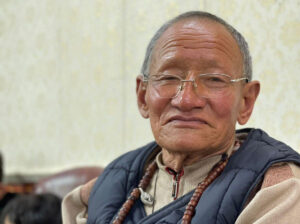

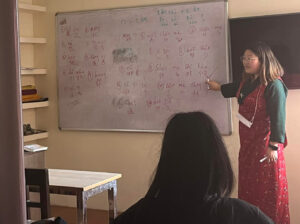

Photo: Pema Zomkyi /Contact

McLeod Ganj is a city swirling with incredible tales. The Kangra Valley with its rolling cedar forests and glowing, molten peaks cradles a resilient Tibetan community, where each person could tell a harrowing story of their family’s exodus across an unforgiving Himalaya icescape or the depravations and hardships that come with day-to-day life as a refugee. So you’d forgive Pema Zomkyi — born to Tibetan parents in Bhutan just as the country made sweeping changes to its refugee policy — for feeling that her life story was nothing remarkable. “I don’t have any special story to tell,” she insists as we sit down to chat in one of McLeod Ganj’s atmospheric cafes.

Hands wrapped around a steaming mug of ginger tea, Pema talks with humility and charm about the path her life has taken, from her birth in Bhutan in the late 1970s to being one of the few female Tibetan web developers working in India today.

“My parents escaped Tibet into Bhutan in the late 1950s and they lived there for 20 years. My mother was from a landlord family, so she had a good life in Tibet. Growing up, she would tell us children stories about what we had, what we’d go back to. It sounded like a lavish lifestyle. She left a lot of things behind, including her parents. But she had to leave otherwise they all would have died. Much later on, someone went back to our village; they found out my grandfather had died of starvation in prison.”

Some 4,000 Tibetans crossed the mountains into Bhutan — one of the harshest routes open to fleeing Tibetans — at the height of the brutal Chinese crackdown in 1959, after which the isolated country of 700,000 citizens shut its borders to refugees. Despite the commonalities between Tibet and Bhutan — ethnically, culturally and religiously — the Bhutanese government put pressure on the Tibetans to better integrate and in 1979 issued them an ultimatum: take citizenships and so renounce their right to return to Tibet, or to leave the country. Around 2,300 accepted the deal, while others — including Pema’s family — uprooted their lives and moved to India.

“We went to Dekyiling colony in Dehradun. Most of the people there came from Bhutan.” She shares an early memory: “Growing up, I knew that if we got independence then we’d go back to Tibet. It was the thing we were hoping for. So when the Nobel Peace Prize was given to His Holiness [in 1989], and my mum and everyone in the colony was celebrating in the streets, us children thought, oh we’ve got independence! People were celebrating that much.” However, this nod of international recognition — which at the time seemed a stepping stone to freedom — did not to alter China’s policy towards Tibet.

She continues: “I came to McLeod Ganj to study at Lower Tibetan Children Village for secondary school, living first with an uncle and then boarding. I was studious, interested in sciences and especially maths. We had a computer lab: I remember we had to remove our shoes, and just learned typing. But still I found it interesting and wanted to do more.” Pema went on to receive a Bachelors in Information Technology from university in Delhi, before returning to Dekyiling to be close to her mother.

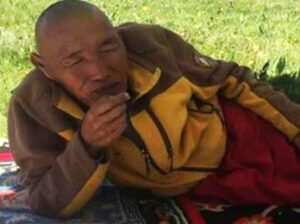

Photo: Elizabeth Mundy / Contact

“When I was at school, we only went home once a year so I wanted to spend time with my family. When you grow up, you start to understand your mum, you start to know her more as an adult. She’s a very strong woman. I have three older brothers and a younger sister: she raised all of us as a single parent, as my father died before we left Bhutan. Even now, I’m in awe: I think, I couldn’t handle five children!” She credits her eldest brother too, now living in Canada, for sacrificing his monkhood at Namgyal Monastery to help provide financially for her education.

Today, she works freelance developing Tibetan websites, after a six-year stint working in IT for the Tibetan government in exile in Dharamshala where she met her husband, a Tibetan from Bylakuppe in south India.

“Politics isn’t for me, but sometimes the world makes you get involved. If you work in Dharamshala — which is the centre of work for the Tibetan struggle —- you get drawn in. Tibetan websites always get hacked, so a big part of my job is security. Right now I’m a consultant for Voice of Tibet radio station, and I have to keep checking the files to secure the website.” Pema adds that her work is made challenging by the fact that Tibetan script is not fully supported on web browsers. “Even with Google, Tibetan text is recognised but not fully integrated — it comes out all congested, not neatly stacked — but they’re working on it. That’s why most of the people here in McLeod Ganj use iPhones: Apple supports our language. It’s progress.”

And how does she find being a woman working in the male-dominated computer industry? “In this community, they encourage women. Tibetans say I can’t believe it! A woman in IT! They’re proud of me.”

We circle back to the topic of Bhutan, which she visited as an adult in 2006. Today, several hundred Tibetans remain undocumented in the country, with limited rights and opportunities. “I think the new generation wish that their parents had taken citizenship because life is difficult. They can’t own their businesses or shops. Here, in India, we can’t apply for government jobs and some companies won’t take us because we’re Tibetans,” she notes regretfully. “It’s a problem. But compared to Bhutan, it’s much better in India.”

Today, among Tibet’s geographical neighbours, India has stood alone as the Tibetan refugees’ ally against the political and economic behemoth of China. “Now, economy is everything. But when that shifts, when the world’s focus isn’t just money, then things will change for us. That’s what we’re hoping.”

Print

Print Email

Email